... del Atlántico!

The actions called for by the EZLN in support of Oaxaca were supposed to take place yesterday, December 22. In Madrid, however, the protest happened on the 20th. Why? Clara Redal, one of the event's organizers and a member of the Comisión Confederal de Solidaridad con Chiapas, explained the date change by pointing out the fact that the 22nd is the day when "aquí, todos se van a su pueblo."

In the context of worldwide, coordinated mobilizations, I read this move as a piece (however superfluous or limited) of the process of building the local autonomies that the Otra Campaña seeks to support. It's a clear and easy example of the way in which Zapatista thought serves as inspiration instead of top-down, authoritarian mandates. The Otra Campaña allows -- or, better yet, demands -- local flexibility in conjunction with global ties.

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Los oaxaqueños del norte de California construyen una Otra Geografía

Alejandro Reyes

En la ciudad de Santa Rosa, en el norte de California, se realizó ayer el Primer Foro Informativo de Análisis Sobre la Situación de Conflicto en Oaxaca. Más de cien personas, la gran mayoría de origen oaxaqueño, se reunieron para discutir la situación en Oaxaca y promover acciones en solidaridad con el movimiento popular en ese estado.

El foro fue organizado por el Frente Indígena de Organizaciones Binacionales (FIOB), Comité en Apoyo al Movimiento Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (CAMPPO), Congreso Indígena Popular de Oaxaca “Ricardo Flores Magón” (CIPO-RFM), Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA), CHALE y Free Mind Media. También presentes estuvieron organizaciones y medios alternativos como Peace and Justice Center, Colectiva Zapatista Ramona, Comité de Apoyo a Chiapas, Voces Cruzando Fronteras y Pacifica Radio (KPFA).

El foro resultó en un comunicado conjunto que será enviado a la Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (APPO) con varias resoluciones: la decisión colectiva de presionar desde los Estados Unidos a los consulados mexicanos para que se retire la Policía Federal Preventiva del estado y por la destitución del gobernador Ulises Ruiz; la decisión de participar en las movilizaciones planeadas para el 20 de noviembre; manifestarse contra la privatización de la educación; exigir el enjuiciamiento del gobierno de Oaxaca por los crímenes cometidos contra el pueblo oaxaqueño.

Rufino Domínguez, de la FIOB, explicó que el propósito de este movimiento va más allá de la solidaridad con Oaxaca. Lo que se pretende es una comunicación y una participación activas, reconociendo los vínculos estrechos que unen a la población oaxaqueña en Estados Unidos con su estado de origen. La FIOB, aunque está compuesta mayoritariamente de indígenas oaxaqueños, cuenta con miembros de muchos otros pueblos. Así, la organización sirve como mecanismo para la construcción de una “otra geografía” que desconoce las fronteras artificiales del poder y responde a una realidad mucho más compleja. De hecho, fue a partir de un encuentro similar al ocurrido en Santa Rosa que, el 8 de octubre de este año, surgió en Los Angeles la APPO-LA, sección californiana de la Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca.

La diáspora oaxaqueña, resultado de las condiciones de pobreza y marginación en ese estado, ha resultado en iniciativas organizativas importantes tanto en México como en Estados Unidos. Tal es el caso con los pueblos triquis en Baja California, visitados por el Subcomandante Marcos y la Otra Campaña hace un mes. A pesar de las condiciones de pobreza, marginación y discriminación en las que viven, haciendo funcionar la agroindustria del jitomate en esa región, esos pueblos muestran una ejemplar capacidad de resistencia y organización.

El pueblo oaxaqueño continúa luchando contra la arbitrariedad y la violencia de los gobiernos y del capital, contribuyendo para construir un México y un mundo más inclusivo y más justo.

En la ciudad de Santa Rosa, en el norte de California, se realizó ayer el Primer Foro Informativo de Análisis Sobre la Situación de Conflicto en Oaxaca. Más de cien personas, la gran mayoría de origen oaxaqueño, se reunieron para discutir la situación en Oaxaca y promover acciones en solidaridad con el movimiento popular en ese estado.

El foro fue organizado por el Frente Indígena de Organizaciones Binacionales (FIOB), Comité en Apoyo al Movimiento Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (CAMPPO), Congreso Indígena Popular de Oaxaca “Ricardo Flores Magón” (CIPO-RFM), Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA), CHALE y Free Mind Media. También presentes estuvieron organizaciones y medios alternativos como Peace and Justice Center, Colectiva Zapatista Ramona, Comité de Apoyo a Chiapas, Voces Cruzando Fronteras y Pacifica Radio (KPFA).

El foro resultó en un comunicado conjunto que será enviado a la Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (APPO) con varias resoluciones: la decisión colectiva de presionar desde los Estados Unidos a los consulados mexicanos para que se retire la Policía Federal Preventiva del estado y por la destitución del gobernador Ulises Ruiz; la decisión de participar en las movilizaciones planeadas para el 20 de noviembre; manifestarse contra la privatización de la educación; exigir el enjuiciamiento del gobierno de Oaxaca por los crímenes cometidos contra el pueblo oaxaqueño.

Rufino Domínguez, de la FIOB, explicó que el propósito de este movimiento va más allá de la solidaridad con Oaxaca. Lo que se pretende es una comunicación y una participación activas, reconociendo los vínculos estrechos que unen a la población oaxaqueña en Estados Unidos con su estado de origen. La FIOB, aunque está compuesta mayoritariamente de indígenas oaxaqueños, cuenta con miembros de muchos otros pueblos. Así, la organización sirve como mecanismo para la construcción de una “otra geografía” que desconoce las fronteras artificiales del poder y responde a una realidad mucho más compleja. De hecho, fue a partir de un encuentro similar al ocurrido en Santa Rosa que, el 8 de octubre de este año, surgió en Los Angeles la APPO-LA, sección californiana de la Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca.

La diáspora oaxaqueña, resultado de las condiciones de pobreza y marginación en ese estado, ha resultado en iniciativas organizativas importantes tanto en México como en Estados Unidos. Tal es el caso con los pueblos triquis en Baja California, visitados por el Subcomandante Marcos y la Otra Campaña hace un mes. A pesar de las condiciones de pobreza, marginación y discriminación en las que viven, haciendo funcionar la agroindustria del jitomate en esa región, esos pueblos muestran una ejemplar capacidad de resistencia y organización.

El pueblo oaxaqueño continúa luchando contra la arbitrariedad y la violencia de los gobiernos y del capital, contribuyendo para construir un México y un mundo más inclusivo y más justo.

Saturday, November 11, 2006

Letter to the New York Times (unpublished)

To the Editor:

Re "Mexican Forces Move to Retake Oaxaca" (October 29): This article rightly points to Ulises Ruiz's responsibility in causing the confrontation to "spiral out of control." But it leaves out important context. The "unrest" did not begin "as a teachers' strike." In fact, the teachers' union convenes annual strikes, which in the past have regularly led to negotiation and compromise with the government. This time, however, Mr. Ruiz forwent negotiation and unilaterally sent the police to repress—with violent tactics, including helicopters and tear gas. Sunday's violent occupation of the central plaza by federal police must be understood within this trajectory of continuing state repression—characterized by three protester deaths that went unreported in this paper, but appear in the well-regarded Mexican daily La Jornada.

Sincerely,

Daniel Nemser

The writer reports for KPFA-Pacifica Radio on Mexican politics and is a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley.

Re "Mexican Forces Move to Retake Oaxaca" (October 29): This article rightly points to Ulises Ruiz's responsibility in causing the confrontation to "spiral out of control." But it leaves out important context. The "unrest" did not begin "as a teachers' strike." In fact, the teachers' union convenes annual strikes, which in the past have regularly led to negotiation and compromise with the government. This time, however, Mr. Ruiz forwent negotiation and unilaterally sent the police to repress—with violent tactics, including helicopters and tear gas. Sunday's violent occupation of the central plaza by federal police must be understood within this trajectory of continuing state repression—characterized by three protester deaths that went unreported in this paper, but appear in the well-regarded Mexican daily La Jornada.

Sincerely,

Daniel Nemser

The writer reports for KPFA-Pacifica Radio on Mexican politics and is a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley.

Monday, October 30, 2006

The Conquest Continues

by Alejandro Reyes

Today, it would seem difficult to imagine the despair that drove entire villages to collective suicide during the first decades of colonization. How do we understand, from the perspective of mestizo individuality, the collective decision to die, to cease to be, before the implacable violence of a conquest that destroyed the lives, the customs, the dignity, the forms of survival, and the entire universe of the Mexican indigenous peoples? By the middle of the XVI century, the Judge Alonso de Zorita, in his Brief Story of the New Spain, told the terrible story of the Mixe and Chontal people in the sierras of Oaxaca, who decided to stop procreating in order to disappear with dignity from a world in which they no longer fit.

Stories of a distant, dark colonial past, of a brutal conquest and genocide that five centuries of history, a struggle for independence, and a revolution have supposedly overcome. But no.

In the Northern Baja California desert, well into the 21st century we listen to the story of the last Kiliwa Indians on the planet, who have decided, like their Chontal and Mixe brothers and sisters did five centuries ago, to die with dignity before being devoured by the machinery of the new form of conquest. There are only 54 members of the tribe and of those only five speak the almost extinct language. For years they have fought to preserve their lands and their forms of survival. The words of Kiliwa leader, Elias Espinoza, reiterate what the Other Campaign has heard over and over during its travels throughout the country. The changes to the constitution and the PROCEDE —an institution that permits communal lands (ejidos) to be divided and sold— make Indians lose more and more of their lands, allow capitalist pressures to turn indigenous people against one another, and gradually deprive them of their forms of subsistence.

With a shortage of land, without work, without social services —there are no schools, no health centers, no electricity— more and more indigenous people leave their places of origin in search of another life. For the Kiliwa, this means death. In the face of this, the women of the community decided to stop procreating, a gradual, collective suicide to spare their children from having to live through an even more terrible spiritual death.

We heard the story of the Kiliwa in a Cucapá community near Mexicali, where Delegate Zero and the caravan of the Other Campaign arrived this 22 of October. The Cucapá are also being pushed toward extinction. Only three communities survive —one in Sonora, one in Arizona and the one we visited— with a total of less than 300 members. The community survives through fishing, but in 1993 the waters where they fish were declared an ecological reserve. The fishing of curvina, their principle form of subsistence and an age-old practice, is now forbidden. Once again, the prohibition is a death sentence. Since 2000, and especially in recent years, the protection of the waters has become more aggressive. Armed soldiers patrol the region, confiscating any catch and destroying boats.

How can one remain indifferent to the extinction of indigenous peoples, and worse yet, to their collective suicide? How can one not be horrified by the brutality that this system inflicts on the thousands of peoples? How can we begin to understand the insensitivity of a good part of society that does not seem to care for its own people? Catering to economic and political interests, the mass media say nothing, and public opinion looks the other way.

But the Other campaign struggles from below, having as its only weapons the solidarity and creativity of those who refuse to maintain their eyes and ears comfortably closed. After consulting with the village leaders, Delegate Zero announced that during the next fishing season, from the end of February to the end of May, a Zapatista camp would be established in the Cucapá community, and asked for the presence and support of members of the Other Campaign from both sides of the border. The organizing has already begun: in meetings in Tijuana, Mexicali, San Diego, Los Angeles, Oakland and elsewhere, adherents to the Other Campaign have already begun planning the camp. The violence and the brutality caused by neoliberalism are a new form of conquest that day by day annihilates life; the other Campaign is the start of a new form of resistance, built from below. A new form of hope.

Today, it would seem difficult to imagine the despair that drove entire villages to collective suicide during the first decades of colonization. How do we understand, from the perspective of mestizo individuality, the collective decision to die, to cease to be, before the implacable violence of a conquest that destroyed the lives, the customs, the dignity, the forms of survival, and the entire universe of the Mexican indigenous peoples? By the middle of the XVI century, the Judge Alonso de Zorita, in his Brief Story of the New Spain, told the terrible story of the Mixe and Chontal people in the sierras of Oaxaca, who decided to stop procreating in order to disappear with dignity from a world in which they no longer fit.

Stories of a distant, dark colonial past, of a brutal conquest and genocide that five centuries of history, a struggle for independence, and a revolution have supposedly overcome. But no.

In the Northern Baja California desert, well into the 21st century we listen to the story of the last Kiliwa Indians on the planet, who have decided, like their Chontal and Mixe brothers and sisters did five centuries ago, to die with dignity before being devoured by the machinery of the new form of conquest. There are only 54 members of the tribe and of those only five speak the almost extinct language. For years they have fought to preserve their lands and their forms of survival. The words of Kiliwa leader, Elias Espinoza, reiterate what the Other Campaign has heard over and over during its travels throughout the country. The changes to the constitution and the PROCEDE —an institution that permits communal lands (ejidos) to be divided and sold— make Indians lose more and more of their lands, allow capitalist pressures to turn indigenous people against one another, and gradually deprive them of their forms of subsistence.

With a shortage of land, without work, without social services —there are no schools, no health centers, no electricity— more and more indigenous people leave their places of origin in search of another life. For the Kiliwa, this means death. In the face of this, the women of the community decided to stop procreating, a gradual, collective suicide to spare their children from having to live through an even more terrible spiritual death.

We heard the story of the Kiliwa in a Cucapá community near Mexicali, where Delegate Zero and the caravan of the Other Campaign arrived this 22 of October. The Cucapá are also being pushed toward extinction. Only three communities survive —one in Sonora, one in Arizona and the one we visited— with a total of less than 300 members. The community survives through fishing, but in 1993 the waters where they fish were declared an ecological reserve. The fishing of curvina, their principle form of subsistence and an age-old practice, is now forbidden. Once again, the prohibition is a death sentence. Since 2000, and especially in recent years, the protection of the waters has become more aggressive. Armed soldiers patrol the region, confiscating any catch and destroying boats.

How can one remain indifferent to the extinction of indigenous peoples, and worse yet, to their collective suicide? How can one not be horrified by the brutality that this system inflicts on the thousands of peoples? How can we begin to understand the insensitivity of a good part of society that does not seem to care for its own people? Catering to economic and political interests, the mass media say nothing, and public opinion looks the other way.

But the Other campaign struggles from below, having as its only weapons the solidarity and creativity of those who refuse to maintain their eyes and ears comfortably closed. After consulting with the village leaders, Delegate Zero announced that during the next fishing season, from the end of February to the end of May, a Zapatista camp would be established in the Cucapá community, and asked for the presence and support of members of the Other Campaign from both sides of the border. The organizing has already begun: in meetings in Tijuana, Mexicali, San Diego, Los Angeles, Oakland and elsewhere, adherents to the Other Campaign have already begun planning the camp. The violence and the brutality caused by neoliberalism are a new form of conquest that day by day annihilates life; the other Campaign is the start of a new form of resistance, built from below. A new form of hope.

Saturday, October 28, 2006

La conquista sigue... y la resistencia

La continuación de la conquista

Alejandro Reyes

Parece difícil, hoy, imaginar la desesperación que habría llevado a pueblos enteros al suicidio colectivo durante las primeras décadas de la colonia. ¿Cómo entender, desde la perspectiva de la individualidad mestiza, la decisión colectiva de morir, de dejar de ser, ante la violencia implacable de una conquista que destruía las vidas, las costumbres, la dignidad, las formas de supervivencia y el universo entero de los pueblos indios de México? A mediados del siglo XVI, el oidor Alonso de Zorita contaba con espanto, en su Breve relación de la Nueva España, la historia de los pueblos mixes y chontales en las sierras de Oaxaca, quienes decidían dejar de procrear para así desaparecer con dignidad de un mundo en el cual ya no cabían.

Historias de un distante pasado oscuro colonial, de una conquista brutal y genocida que cinco siglos de historia, una lucha de independencia y una revolución supuestamente han superado. Pero no.

En el desierto de Baja California Norte, en pleno siglo XXI, escuchamos la historia de los últimos indígenas kiliwa del planeta, que decidieron, como sus hermanos mixes y chontales hace cinco siglos, morir con dignidad antes de ser devorados por la maquinaria de una nueva forma de conquista. Son sólo 54 miembros de la tribu, y de ellos sólo cinco hablan la casi extinta lengua. Durante años han luchado por preservar sus tierras y su forma de subsistencia. Las palabras del líder kiliwa Elías Espinoza reiteran lo que la Otra Campaña ha escuchado una y otra vez durante su recorrido por el país. Los cambios a la constitución y la institución del Procede, que permiten que las tierras comunitarias (ejidos) se dividan y se vendan, hacen que los indios pierdan más y más sus tierras, que las presiones de los capitalistas enfrenten a los indígenas entre sí, que se vayan perdiendo las formas de subsistencia. Con escasez de tierras, sin trabajo, sin servicios —no hay escuelas, centros de salud, electricidad—, más y más indígenas dejan su lugar de origen en busca de otra vida. Para los kiliwa, esto significa la muerte. Ante esto, las mujeres de la comunidad decidieron dejar de procrear, un suicidio colectivo para evitar que sus hijos vivieran una mucho más terrible muerte espiritual.

Escuchamos la historia de los kiliwas en una comunidad cucapá, cerca de Mexicali, adonde llegó el Delegado Zero y la karavana de la Otra Campaña este 22 de octubre. Los cucapá también están en proceso de extinción. Sobreviven sólo tres comunidades —una en Sonora y otra en Arizona, además de la que visitamos—, con un total de menos de 300 miembros. La comunidad vive de la pesca, pero en 1993 las aguas donde pescan se convirtieron en reserva ecológica. La pesca de la curvina, su principal medio de subsistencia y práctica milenaria, ahora está prohibida. Y nuevamente, la prohibición es una sentencia de muerte. A partir del 2000, y sobre todo recientemente, la protección de las aguas se ha vuelto más agresiva. Soldados armados patrullan la región, confiscando la pesca y destruyendo los barcos.

¿Cómo mantenerse impávido ante la extinción de los pueblos indios, y más, ante su suicidio colectivo? ¿Cómo no ver con horror lo que la brutalidad de este sistema hace con miles de pueblos hermanos? ¿Cómo explicar la insensibilidad de buena parte de la población, que ni siquiera ve a su propia gente? Al servicio de intereses económicos y políticos, los medios masivos de comunicación nada dicen, y la opinión pública se hace la desentendida.

Pero la Otra Campaña lucha desde abajo teniendo como única arma la solidaridad y la creatividad de aquellos que se rehúsan a mantener ojos y oídos cómodamente cerrados. Después de una consulta con líderes del pueblo, el Delegado Zero anunció que durante la próxima temporada de pesca, de finales de febrero a finales de mayo, un campamento zapatista se establecería en la comunidad cucapá, y pidió la presencia y el apoyo a miembros de la Otra Campaña en ambos lados de la frontera. Y la organización ya comenzó: en reuniones en Tijuana, Mexicali, San Diego, Los Angeles, Oakland y otros lados, adherentes a la Otra Campaña ya empezaron a planear el campamento. La violencia y el brutal despojo causados por el neoliberalismo son una nueva forma de conquista que día a día aniquila a los pueblos; la Otra Campaña es el inicio de una nueva forma de resistencia, construida desde abajo. Una nueva forma de esperanza.

Alejandro Reyes

Parece difícil, hoy, imaginar la desesperación que habría llevado a pueblos enteros al suicidio colectivo durante las primeras décadas de la colonia. ¿Cómo entender, desde la perspectiva de la individualidad mestiza, la decisión colectiva de morir, de dejar de ser, ante la violencia implacable de una conquista que destruía las vidas, las costumbres, la dignidad, las formas de supervivencia y el universo entero de los pueblos indios de México? A mediados del siglo XVI, el oidor Alonso de Zorita contaba con espanto, en su Breve relación de la Nueva España, la historia de los pueblos mixes y chontales en las sierras de Oaxaca, quienes decidían dejar de procrear para así desaparecer con dignidad de un mundo en el cual ya no cabían.

Historias de un distante pasado oscuro colonial, de una conquista brutal y genocida que cinco siglos de historia, una lucha de independencia y una revolución supuestamente han superado. Pero no.

En el desierto de Baja California Norte, en pleno siglo XXI, escuchamos la historia de los últimos indígenas kiliwa del planeta, que decidieron, como sus hermanos mixes y chontales hace cinco siglos, morir con dignidad antes de ser devorados por la maquinaria de una nueva forma de conquista. Son sólo 54 miembros de la tribu, y de ellos sólo cinco hablan la casi extinta lengua. Durante años han luchado por preservar sus tierras y su forma de subsistencia. Las palabras del líder kiliwa Elías Espinoza reiteran lo que la Otra Campaña ha escuchado una y otra vez durante su recorrido por el país. Los cambios a la constitución y la institución del Procede, que permiten que las tierras comunitarias (ejidos) se dividan y se vendan, hacen que los indios pierdan más y más sus tierras, que las presiones de los capitalistas enfrenten a los indígenas entre sí, que se vayan perdiendo las formas de subsistencia. Con escasez de tierras, sin trabajo, sin servicios —no hay escuelas, centros de salud, electricidad—, más y más indígenas dejan su lugar de origen en busca de otra vida. Para los kiliwa, esto significa la muerte. Ante esto, las mujeres de la comunidad decidieron dejar de procrear, un suicidio colectivo para evitar que sus hijos vivieran una mucho más terrible muerte espiritual.

Escuchamos la historia de los kiliwas en una comunidad cucapá, cerca de Mexicali, adonde llegó el Delegado Zero y la karavana de la Otra Campaña este 22 de octubre. Los cucapá también están en proceso de extinción. Sobreviven sólo tres comunidades —una en Sonora y otra en Arizona, además de la que visitamos—, con un total de menos de 300 miembros. La comunidad vive de la pesca, pero en 1993 las aguas donde pescan se convirtieron en reserva ecológica. La pesca de la curvina, su principal medio de subsistencia y práctica milenaria, ahora está prohibida. Y nuevamente, la prohibición es una sentencia de muerte. A partir del 2000, y sobre todo recientemente, la protección de las aguas se ha vuelto más agresiva. Soldados armados patrullan la región, confiscando la pesca y destruyendo los barcos.

¿Cómo mantenerse impávido ante la extinción de los pueblos indios, y más, ante su suicidio colectivo? ¿Cómo no ver con horror lo que la brutalidad de este sistema hace con miles de pueblos hermanos? ¿Cómo explicar la insensibilidad de buena parte de la población, que ni siquiera ve a su propia gente? Al servicio de intereses económicos y políticos, los medios masivos de comunicación nada dicen, y la opinión pública se hace la desentendida.

Pero la Otra Campaña lucha desde abajo teniendo como única arma la solidaridad y la creatividad de aquellos que se rehúsan a mantener ojos y oídos cómodamente cerrados. Después de una consulta con líderes del pueblo, el Delegado Zero anunció que durante la próxima temporada de pesca, de finales de febrero a finales de mayo, un campamento zapatista se establecería en la comunidad cucapá, y pidió la presencia y el apoyo a miembros de la Otra Campaña en ambos lados de la frontera. Y la organización ya comenzó: en reuniones en Tijuana, Mexicali, San Diego, Los Angeles, Oakland y otros lados, adherentes a la Otra Campaña ya empezaron a planear el campamento. La violencia y el brutal despojo causados por el neoliberalismo son una nueva forma de conquista que día a día aniquila a los pueblos; la Otra Campaña es el inicio de una nueva forma de resistencia, construida desde abajo. Una nueva forma de esperanza.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

Radio Zapatista

The latest program is up on our website, a half-hour in English, which aired live last Friday. We discuss the immigrants' rights rally last Monday in San Francisco and the role of the elite (and often "liberal") politicians and media pundits.

In other news, we will be having an event at La Peña (Berkeley) about our trip through Mexico this summer, with music, pictures, video, and discussion:

In other news, we will be having an event at La Peña (Berkeley) about our trip through Mexico this summer, with music, pictures, video, and discussion:

Radio Zapatista

Returns from Chiapas

Thursday September 28, 2006

$5-$10 sliding scale - 7:30pm

Report from Mexico on Atenco, the Elections & the Other Campaign, slides & video. Benefit for Health Care in Autonomous Zapatista Communities. Sponsored by the Chiapas Support Committee.

Sunday, September 03, 2006

First live program back in the Bay Area

This Friday we did our first live program back at the Mission district in San Francisco: a 1-hour program about the situation in Mexico, repression, the role of mass media and alternative media, Oaxaca, etc. We interviewed Lucas Alvarez from Radio 620 AM in Mexico City, who was censured by the federal government for broadcasting together with Subcomandante Marcos this July.

Este viernes hicimos nuestro primer programa en vivo de regreso a las entrañas del imperio, en el barrio de la Misión, San Panchito: un programa de 1 hora sobre la situación en México, la represión, los medios de comunicación, Oaxaca, etc. Entrevistamos a Lucas Álvarez de Radio 620 AM en el DF, cuyo programa Política de Banqueta fue censurado en julio por el gobierno federal por la participación del Subcomandante Marcos.

Escucha el programa/Listen to the program.

Este viernes hicimos nuestro primer programa en vivo de regreso a las entrañas del imperio, en el barrio de la Misión, San Panchito: un programa de 1 hora sobre la situación en México, la represión, los medios de comunicación, Oaxaca, etc. Entrevistamos a Lucas Álvarez de Radio 620 AM en el DF, cuyo programa Política de Banqueta fue censurado en julio por el gobierno federal por la participación del Subcomandante Marcos.

Escucha el programa/Listen to the program.

The Other Side of the Red Alert / Otra mirada a la alerta roja

US journalist John Ross recently unleashed a storm of controversy with an article that criticized the EZLN's Red Alert. As a response to his criticism, I wrote the following article, published by the Center for Economic and Political Research for Community Action (CIEPAC) in Chiapas.

The Other Side of the Red Alert

Un artículo reciente del periodista estadounidense John Ross provocó una sonada controversia por las críticas que hace a la Alerta Roja decretada por el EZLN en mayo pasado. Como respuesta a sus críticas, escribí el siguiente artículo, publicado por el Centro de Investigaciones Económicas y Políticas de Acción Comunitaria (CIEPAC), Chiapas.

Otra mirada a la Alerta Roja.

The Other Side of the Red Alert

Un artículo reciente del periodista estadounidense John Ross provocó una sonada controversia por las críticas que hace a la Alerta Roja decretada por el EZLN en mayo pasado. Como respuesta a sus críticas, escribí el siguiente artículo, publicado por el Centro de Investigaciones Económicas y Políticas de Acción Comunitaria (CIEPAC), Chiapas.

Otra mirada a la Alerta Roja.

Friday, September 01, 2006

Letter to the SF Chronicle (unpublished)

To the Editor:

Re “Angry Days in Mexico” (editorial, Sept. 1): Having spent the last three months traveling through Mexico as an investigative reporter for KPFA, I feel the need to question some of the editorial board’s assertions. Such as the claim that Lopez Obrador “has run out of legal ways” to contest the elections, “so he's starting to seek illegal ones.” It’s not exactly an untrue statement (although I haven’t anything suggesting that the PRD candidate is urging people to break the law), but the underlying assumptions betray the naivety of this political stance: if the law doesn’t work, if elections can be (and historically have been) fraudulent, then staying within the “legal” loses all meaning.

Then there’s the claim that Lopez Obrador is actively seeking violent confrontation because it’s the only way to boost his ratings “just as a violent teachers' strike in Oaxaca has soured the public on that state's governor.” The teachers’ strike, however, was entirely peaceful, until the government sent shock troops to batter, evict, and arrest them. The violence in Oaxaca comes from the state, as it does in Mexico City, where police have attacked and evicted peaceful PRD protesters in front of the government palace. It would be worth keeping this in mind when thinking about the electoral crisis in Mexico.

Sincerely,

Daniel Nemser

Re “Angry Days in Mexico” (editorial, Sept. 1): Having spent the last three months traveling through Mexico as an investigative reporter for KPFA, I feel the need to question some of the editorial board’s assertions. Such as the claim that Lopez Obrador “has run out of legal ways” to contest the elections, “so he's starting to seek illegal ones.” It’s not exactly an untrue statement (although I haven’t anything suggesting that the PRD candidate is urging people to break the law), but the underlying assumptions betray the naivety of this political stance: if the law doesn’t work, if elections can be (and historically have been) fraudulent, then staying within the “legal” loses all meaning.

Then there’s the claim that Lopez Obrador is actively seeking violent confrontation because it’s the only way to boost his ratings “just as a violent teachers' strike in Oaxaca has soured the public on that state's governor.” The teachers’ strike, however, was entirely peaceful, until the government sent shock troops to batter, evict, and arrest them. The violence in Oaxaca comes from the state, as it does in Mexico City, where police have attacked and evicted peaceful PRD protesters in front of the government palace. It would be worth keeping this in mind when thinking about the electoral crisis in Mexico.

Sincerely,

Daniel Nemser

Thursday, August 10, 2006

Letter to the Editor, San Francisco Chronicle (unpublished)

To the Editor:

Re "Political Unrest Slows Tourism in Mexico" (Aug. 4): I recently returned to the Bay Area from a two and a half month trip through Mexico doing reporting for KPFA, and I can assure you that what I saw has nothing to do with the images painted in the article. It states, for example, that in Oaxaca "tourists must pass through checkpoints" to enter the main square. Not once was I "checked" or my path blocked. What's more, the Oaxacan teachers' movement has gone far out of its way to include tourists in its efforts -- the plaza features kiosks where college students fluent in English offer free explanations, while others distribute posters and pamphlets in English, French, German, and Italian. The coverage of the Mexico City protests is equally flimsy. It seems the author did not venture very far outside of his hotel, let alone speak with protesters, but rather relied solely on interviews with tourist industry officials. Finally, the arbitrary links to drug trafficking in Acapulco -- which has absolutely nothing to do with the "political unrest" of the headline -- strike me as notably out of place.

Sincerely,

Daniel Nemser

The author is a graduate student in Latin American literature and history at the University of California, Berkeley.

Re "Political Unrest Slows Tourism in Mexico" (Aug. 4): I recently returned to the Bay Area from a two and a half month trip through Mexico doing reporting for KPFA, and I can assure you that what I saw has nothing to do with the images painted in the article. It states, for example, that in Oaxaca "tourists must pass through checkpoints" to enter the main square. Not once was I "checked" or my path blocked. What's more, the Oaxacan teachers' movement has gone far out of its way to include tourists in its efforts -- the plaza features kiosks where college students fluent in English offer free explanations, while others distribute posters and pamphlets in English, French, German, and Italian. The coverage of the Mexico City protests is equally flimsy. It seems the author did not venture very far outside of his hotel, let alone speak with protesters, but rather relied solely on interviews with tourist industry officials. Finally, the arbitrary links to drug trafficking in Acapulco -- which has absolutely nothing to do with the "political unrest" of the headline -- strike me as notably out of place.

Sincerely,

Daniel Nemser

The author is a graduate student in Latin American literature and history at the University of California, Berkeley.

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

Legal Victory for SCF!

Great news from the LA Times:

South Los Angeles urban farmers scored their first victory in court Wednesday in their last-ditch effort to regain what used to be a lush community garden in a rough industrial area.

Judge Helen I. Bendix ruled that developer Ralph Horowitz could not exclude evidence about the deal he made with the city of Los Angeles in 2003.

The farmers' attorneys accuse the city and Horowitz of making a back-door deal to resell the land to Horowitz, a move they said violated their constitutional right of due process.

(...)

If a jury rules in the farmers' favor, Horowitz's land would revert to the city, and officials could then decide whether to restore the gardens.

(Unpublished) Letter to the New York Times

July 16, 2006

To the Editor:

Ginger Thompson's most recent article on the Mexican election ("Crowds Rally Again to Demand Recount in Mexico," July 17) repeatedly highlights the potential for violence that could be "unleashed" from Lopez Obrador's supporters. But it fails to acknowledge the real threat of violence if Felipe Calderon's victory is affirmed. Only Calderon actively approved of the government's violent repression in San Salvador Atenco on May 4, where police killed two youths and tortured, sexually abused, and indiscriminately arrested hundreds.

Daniel Nemser

Mexico City, Mexico

The writer has been covering the Mexican elections for KPFA - Pacifica Radio, and is a graduate student in Latin American Studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

To the Editor:

Ginger Thompson's most recent article on the Mexican election ("Crowds Rally Again to Demand Recount in Mexico," July 17) repeatedly highlights the potential for violence that could be "unleashed" from Lopez Obrador's supporters. But it fails to acknowledge the real threat of violence if Felipe Calderon's victory is affirmed. Only Calderon actively approved of the government's violent repression in San Salvador Atenco on May 4, where police killed two youths and tortured, sexually abused, and indiscriminately arrested hundreds.

Daniel Nemser

Mexico City, Mexico

The writer has been covering the Mexican elections for KPFA - Pacifica Radio, and is a graduate student in Latin American Studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

Monday, July 17, 2006

Pictures (personal edition)

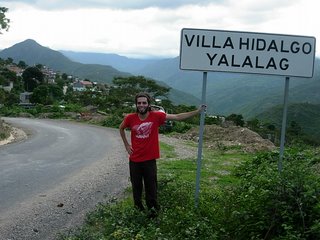

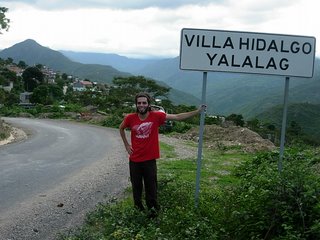

Some pictures from the last few days' jaunt to the Sierra Juarez (here's Alejandro's piece in Spanish on the trip).

This one's a little different. A compa we met in Oaxaca, who works at the Universidad de la Tierra. In the photo, from left to right, Daniel, Daniel Alejandro, Alejandro. I think this goes nicely with the picture of our friends from Agua Prieta.

This one's a little different. A compa we met in Oaxaca, who works at the Universidad de la Tierra. In the photo, from left to right, Daniel, Daniel Alejandro, Alejandro. I think this goes nicely with the picture of our friends from Agua Prieta.

This one's a little different. A compa we met in Oaxaca, who works at the Universidad de la Tierra. In the photo, from left to right, Daniel, Daniel Alejandro, Alejandro. I think this goes nicely with the picture of our friends from Agua Prieta.

This one's a little different. A compa we met in Oaxaca, who works at the Universidad de la Tierra. In the photo, from left to right, Daniel, Daniel Alejandro, Alejandro. I think this goes nicely with the picture of our friends from Agua Prieta.

Sunday, July 16, 2006

Yalalaag, Villa Alta

El tiempo pasa y no pasa, se alarga, se estrecha, se encoje, se tira boca arriba y se hace el muerto, después se lanza precipitadamente por el abismo y levanta el vuelo antes de perderse en la nada... Yalalaag: hace más de una década estaba yo sentado frente a la plaza esperando el autobus rumbo a Oaxaca, pensando precisamente cómo el tiempo se acorta y se alarga, cómo se nos va entre las manos como agua. Más de una década después y ahi estamos, Daniel y yo (fue Lucas en aquellos tiempos), y después del largo viaje, sudorosos, cansados, medio atarantados de tanta terracería, deslumbrados ante tanta inmensidad y tanta belleza, y después de la larga espera en la casa de la dueña donde nos vienen a hablar tres generaciones de mujeres, la más chica nos lleva hacia la misma casa donde hace tres lustros estuve, al mismo patio repleto de flores, al mismo cuarto, las mismas paredes, las mismas camas, como si el tiempo se hubiera detenido en la inmobilidad de ese espacio. Pero eso es acá, dentro de estas paredes, porque allá afuera el tiempo se viene saltando y dando maromas y haciendo un desmadre de los mil diablos, porque en todo esto resulta que llegó la carretera, casi casi el pavimento llega hasta acá, y las remesas, y los que van y vienen del "otro lado"... qué lado, si fuera de estas montañas todo es "otro", mundos infinitamente distantes que de repente se encuentran en el choque de culturas asíncronas, disonantes... polifonía delirante, cacofonía o quizás una nueva forma de creatividad, nuevos entendimientos. En Villa Alta el rectángulo de concreto que albergaba múltiples cuartitos separados por enclenques tablas de madera se convirtió en hotel de tres pisos, con patio central y televisión a todo volumen. Ni sombra del pasado, pero los comedores ahí están, frente al quiosco, y las montañas, el verdor, la inmensidad nebulosa... Ahora hay terminal camionera, un hospital, un puesto de gasolina. Los niños juegan futbol en el zócalo y se les unen dos adolescentes con tacones y sus mejores ropas, indecisas entre ser niñas y ser mujeres. Cuántos aquí han ido y han regresado: Ohio, California... Don José nos cuenta que su hijo está en San Diego, y le ofrezco llevarle una carta. De manera que más tarde nos encontramos en el minúsculo cuartito donde Doña Cecilia nos ofrece pepitas y don José me explica trabajosamente lo que quiere que le ponga en la carta, en un idioma cargado de zapoteco, en un idioma que habla de otro universo, de otro tiempo, de otro pensar... Y la plática es triste, por el descompaso de los tiempos. Que por qué nunca le habla su hijo, para poder contarle del terrenito, pa decirle que se venga ya para construir su casita y preparar la milpa, pos ni modo que se la pase toda la vida sin su casita, sin su milpa... Ahi se fue hace tiempo don José a San Diego, ve tú a saber cómo fue que llegó hasta allá, con qué dinero cruzó, cómo diablos encontró a su hijo, si ni leer sabe el hombre, si no entiende de direcciones ni de ciudades y mucho menos de lo que es ese monstruo llamado Otro Lado... Pero el hijo le pidió que no se quedara, que cómo se iba a quedar, que se regresara para su tierra, para Oaxaca, para Villa Alta, para su mujer y su milpa, para el fin de mundo en la sierra donde está la tierra, la raíz, el orígen. Me ofrecen mucho dinero por el terreno pero yo no lo vendo, nos dice, porque la tierra no se vende. La tierra no se vende. La tierra es vida. Es vida. Y es para el hijo que no va a regresar, que vive en San Ysidro, que tiene cuatro hijos nacidos en el lado de allá, que tiene su vida lejana... Don José y Doña Cecilia nos regalan su hospitalidad, su corazón, su silencio, y nos vamos cargados de agradecimiento y tristeza... Noche insomne: soledad lucha pobreza injusticia los tiempos que se dilatan y se contraen cambios permanencias posibilidades perplejidades zapatismo lucha lucha y la familia desgarrada intolerancia mano dura yo yo privilegios egoismo y dónde quedó la compasión dónde dónde quedó dónde quedó adónde se fue dónde dónde... , Amanece brumoso el día, en la mañana pésimo café y excelentes tortillas y amabilidad oaxaqueña y despedida de la sierra, siempre la sierra, siempre el adiós y el retorno... y en la bruma, la lluvia, el lodo, cañadas, bosques y soledad, la moto ruge en el verde silencio hasta que se despeja el cielo y aparece la inmensidad recién lavada de la sierra mixe y un changarrito de madera y un café y pan dulce y un jardín florido y el descenso rumbo a la urbe y el impetuoso quehacer de los hombres...

Pictures

Nice juxtaposition between people eating in the portales and the slogans of the planton in the background.

Nice juxtaposition between people eating in the portales and the slogans of the planton in the background. Alternative, independent "radio," adherents to the Other Campaign, blasting into the zocalo.

Alternative, independent "radio," adherents to the Other Campaign, blasting into the zocalo. For the tourists...

For the tourists... Oaxacan graffiti.

Oaxacan graffiti.

New Article on SCF / Nuevo artículo sobre la Granja Sur Central

Check out my article on the South Central Farm, published by CIEPAC. (Versión en español aquí -- Muchísimas gracias a Miguel Pickard por su ayuda editorial y de traducción!)

Thursday, July 13, 2006

La Comuna de Oaxaca (?)

Caminamos ingenuamente de la rústica posada donde nos alojamos rumbo al centro por las calles coloniales de esta querida Oaxaca, ciudad de tantas visitas anteriores, ciudad de hospitalidad y resistencia, de orgullo y amabilidad, de un pueblo sereno, profundo, abierto y al mismo tiempo impenetrable; ciudad de arquitectura espléndida y de sincretismo barroco, de música y poesía.

Pero digo que ingenuamente caminamos porque, aunque Hermann ya nos había contado, con exaltada elocuencia, lo que los maestros y la sociedad oaxaqueña está haciendo aquí, lo extraordinario de todo esto de alguna manera no registró, las palabras se quedan atrapadas en los vericuetos de la abstracción y de alguna manera no penetran la coraza de la realidad. Pero entonces llegamos a las barricadas, frágiles barreras de lámina y, en algunos lugares, nada más que simbólicas, cordones que ninguna resistencia podrían oponer a una invasión policial. Pero transponer el umbral es como entrar (o por lo menos así lo fue para nosotros) en una especie de territorio liberado oaxaqueño, donde expresiones de repudio al sistema político y de conciencia social, ausentes en el resto del territorio mexicano, florecen en el arte, en los murales, en las pancartas y lonas, en los videos y la música que venden los ambulantes, en las conversaciones de los miles de profesores y miembros de la sociedad civil que se han instalado en el zócalo y en las calles aledañas... Anarquistas, marxistas, zapatistas, sindicalistas, ONGeros, maestros y maestras, amas de casa, trabajadores, vendedores ambulantes, etc., ocupan el centro con un ambiente festivo donde la palabra fluye, donde la censura existe apenas en la forma agazapada de los policías clandestinos, los orejas, los mirones que por ahí andan infiltrados y que todos reconocen.

En los siguientes días platicamos con maestr@s, activistas, académic@s y demás. Escuchamos las historias de la represión del 14 de junio, cuando, a las 4 de la mañana, 2000 a 2500 policías invadieron el centro de la ciudad en un operativo violento diseñado no sólo para desalojar el centro, sino para instigar el miedo, muy al estilo de Atenco, aunque ciertamente de proporciones más limitadas (seguramente debido a la ausencia de la policía federal). Uno de los primeros blancos de la represión fue Radio Plantón. Les cayeron pesado a los compas, lo que no destruyeron se lo robaron, y se llevaron presos a tres de ellos, con sus buenos macanazos. A los miles de personas que estaban en el plantón los dispersaron a base de golpes, humillaciones y gases lacrimógenos. Nos cuentan del aborto de una maestra embarazada, y de la muerte de por lo menos un niño, aunque los testimonios de muerte son ambiguous y nadie sabe exactamente si los hubo.

Fuimos a Radio Plantón con la intención de entrevistarlos; pero nos voltearon la cosa y termiaron entrevistándonos a nosotros, en un programa en vivo de una hora, en la cual fluyó el intercambio entre Radio Zapatista y Radio Plantón. Dos días después estuvimos también en un programa de Radio Plantón con los compas de Banda Ancha, un programa de la banda de la UniTierra, irreverentes y desmadrosos... geniales.

Escuchen el programa de Radio Plantón y Radio Zapatista.

Pero digo que ingenuamente caminamos porque, aunque Hermann ya nos había contado, con exaltada elocuencia, lo que los maestros y la sociedad oaxaqueña está haciendo aquí, lo extraordinario de todo esto de alguna manera no registró, las palabras se quedan atrapadas en los vericuetos de la abstracción y de alguna manera no penetran la coraza de la realidad. Pero entonces llegamos a las barricadas, frágiles barreras de lámina y, en algunos lugares, nada más que simbólicas, cordones que ninguna resistencia podrían oponer a una invasión policial. Pero transponer el umbral es como entrar (o por lo menos así lo fue para nosotros) en una especie de territorio liberado oaxaqueño, donde expresiones de repudio al sistema político y de conciencia social, ausentes en el resto del territorio mexicano, florecen en el arte, en los murales, en las pancartas y lonas, en los videos y la música que venden los ambulantes, en las conversaciones de los miles de profesores y miembros de la sociedad civil que se han instalado en el zócalo y en las calles aledañas... Anarquistas, marxistas, zapatistas, sindicalistas, ONGeros, maestros y maestras, amas de casa, trabajadores, vendedores ambulantes, etc., ocupan el centro con un ambiente festivo donde la palabra fluye, donde la censura existe apenas en la forma agazapada de los policías clandestinos, los orejas, los mirones que por ahí andan infiltrados y que todos reconocen.

En los siguientes días platicamos con maestr@s, activistas, académic@s y demás. Escuchamos las historias de la represión del 14 de junio, cuando, a las 4 de la mañana, 2000 a 2500 policías invadieron el centro de la ciudad en un operativo violento diseñado no sólo para desalojar el centro, sino para instigar el miedo, muy al estilo de Atenco, aunque ciertamente de proporciones más limitadas (seguramente debido a la ausencia de la policía federal). Uno de los primeros blancos de la represión fue Radio Plantón. Les cayeron pesado a los compas, lo que no destruyeron se lo robaron, y se llevaron presos a tres de ellos, con sus buenos macanazos. A los miles de personas que estaban en el plantón los dispersaron a base de golpes, humillaciones y gases lacrimógenos. Nos cuentan del aborto de una maestra embarazada, y de la muerte de por lo menos un niño, aunque los testimonios de muerte son ambiguous y nadie sabe exactamente si los hubo.

Fuimos a Radio Plantón con la intención de entrevistarlos; pero nos voltearon la cosa y termiaron entrevistándonos a nosotros, en un programa en vivo de una hora, en la cual fluyó el intercambio entre Radio Zapatista y Radio Plantón. Dos días después estuvimos también en un programa de Radio Plantón con los compas de Banda Ancha, un programa de la banda de la UniTierra, irreverentes y desmadrosos... geniales.

Escuchen el programa de Radio Plantón y Radio Zapatista.

South Central Farm

Yesterday the farmers went to court:

LOS ANGELES -- The battle over the South Central Farm moved to court Wednesday, with a judge hearing arguments on whether a trial should be held in a lawsuit over the city's 2003 sale of the land to developer Ralph Horowitz.It seems like it's still too soon to tell anything, but in the meantime there's a fantastic new article, full of details, up at the SCF website. If you've got any questions about any part of the farm struggle, check it out.

The farmers filed a class-action suit against the city of Los Angeles and Horowitz in February 2004, arguing the sale should be nullified on grounds that there was no prior public notice.

The farmers claim in court papers they might have been able to raise funds to buy the land themselves had they known the land was available.

Thursday, July 06, 2006

La Plenaria

El día después de llegar fuimos a la reunión de la Asamblea Metropolitana de la Otra Campaña, donde decidieron entregar una propuesta para hacer una marcha el día 2 de julio, el día de la elección. Nos sentíamos un poco incómodos con esto, porque nos habían comentado que era ilegal hacer cualquier tipo de acción “que impidiera el proceso electoral” y que el ejército estaría presente para “mantener la calma.” Y la verdad es que no vimos la manera en que se tomó esta decisión, aunque luego nos comentó John Gibler de que fue una minoría estudiantil que había forzado el voto sobre la marcha donde salieron ganando, sin que hubiera consenso. Siempre sabíamos que no hubo consenso, pero no exactamente cómo se tomó la decisión.

La propuesta de hacer una marcha era exactamente ésta: una propuesta. La idea era que la propuesta tenía que llegar a la Asamblea Nacional, junta con otras propuestas sobre acciones posibles para, en las palabras del Subcomandante Marcos, “irrumpir” (o, como luego explicó, aparecer) en el calendario electoral. Pero no ocurrió así. De hecho, después de la decisión de la Metropolitana empezaron a circularse volantes llamando al pueblo a la marcha planeada para el 2 -- como si ya la hubiera aprobado la Asamblea Nacional. Incluso durante un evento en la UAM-Xochimilco, el moderador, al presentar al Delegado Zero, también mencionó que iba a haber la marcha, y Marcos no lo contradijo. No dijo nada. Y todo esto, pues, antes de que la Asamblea Nacional ni siquiera hubiera comenzado.

No obstante todo esto, la propia Asamblea fue muy interesante. Un experimento en la democracia participativa, y lo fascinante es que todos sabemos que la Otra Campaña es un proceso y que complicaciones deben de esperarse. La idea, sencillamente, es que vamos a superarlas.

La cuestión es cuándo.

La primera parte de la Asamblea estaba dedicada a los informes de los diferentes estados del país (y también el otro lado), además de reportes sectoriales (mujeres, indígenas, trabajadoras sexuales, hasta niños incluso dieron ponencias). Ocupó más o menos todo el primer día, pero con apenas 30 minutos quedando la mesa decidió tomar una decisión sobre la marcha del 2 de julio. Casi nadie escuchaba las propuestas, de que no había muchas, y no había tiempo para ningún tipo de debate. Efectivamente forzaron un voto y, parecido a la manera en que se tomó la decisión dentro de la Metropolitana, igual ocurrió en la Nacional.

Al día siguiente, una gran variedad de gente se levantó a reclamar este proceso. Manifestaron su desacuerdo con estos procedimientos y trataron de meter algunas otras propuestas. Con estos reclamos también empezaron contrareclamos y todo esto ocupó mucho tiempo, hasta la hora de la comida. Luego del almuerzo, el sup se puso a hablar, criticando también la influencia no representativa del DF y el Estado de México en la reunión, pero tampoco cuestionando la decisión de hacer la marcha. Sin embargo, metió su propia propuesta para la marcha, jugando un papel interesantísimo entre líder autoritario y, para usar un término que nos explicó Rodrigo Ibarra, un “anciano” que busca alternativas incluyentes que faciliten la conciliación de la comunidad. O sea que la propuesta del Delegado Zero nunca cuestionó la marcha, pero al mismo tiempo pidió que los bloques regionales se reunieran para escribir el texto que se iba a leer en el Zócalo al día siguiente, y también que eligieran las personas que lo iban a leer. Desde luego, la figura moral de Marcos consiguió un casi consenso, aunque había borrado varias contrapropuestas que andaban por allí. Y la verdad es que, para mí, las reuniones en bloque fueron la parte más chida, porque facilitó la participación de las personas que aún no habían ofrecido sus comentarios y sus voces dentro del auditorio enorme. Nos pusimos las pilas y empezamos a trabajar, democráticamente y de abajo… pero impulsados por el “líder” (o anciano). Una tensión fascinante.

Y después de todo esto, la marcha estuvo buenísima, muy divertida, llena de movida, y empoderadora. Sin problemas por parte de la policía. Hay algunas fotos aquí, y tal vez vienen más. Y a ver que dice Alejandro...

La propuesta de hacer una marcha era exactamente ésta: una propuesta. La idea era que la propuesta tenía que llegar a la Asamblea Nacional, junta con otras propuestas sobre acciones posibles para, en las palabras del Subcomandante Marcos, “irrumpir” (o, como luego explicó, aparecer) en el calendario electoral. Pero no ocurrió así. De hecho, después de la decisión de la Metropolitana empezaron a circularse volantes llamando al pueblo a la marcha planeada para el 2 -- como si ya la hubiera aprobado la Asamblea Nacional. Incluso durante un evento en la UAM-Xochimilco, el moderador, al presentar al Delegado Zero, también mencionó que iba a haber la marcha, y Marcos no lo contradijo. No dijo nada. Y todo esto, pues, antes de que la Asamblea Nacional ni siquiera hubiera comenzado.

No obstante todo esto, la propia Asamblea fue muy interesante. Un experimento en la democracia participativa, y lo fascinante es que todos sabemos que la Otra Campaña es un proceso y que complicaciones deben de esperarse. La idea, sencillamente, es que vamos a superarlas.

La cuestión es cuándo.

La primera parte de la Asamblea estaba dedicada a los informes de los diferentes estados del país (y también el otro lado), además de reportes sectoriales (mujeres, indígenas, trabajadoras sexuales, hasta niños incluso dieron ponencias). Ocupó más o menos todo el primer día, pero con apenas 30 minutos quedando la mesa decidió tomar una decisión sobre la marcha del 2 de julio. Casi nadie escuchaba las propuestas, de que no había muchas, y no había tiempo para ningún tipo de debate. Efectivamente forzaron un voto y, parecido a la manera en que se tomó la decisión dentro de la Metropolitana, igual ocurrió en la Nacional.

Al día siguiente, una gran variedad de gente se levantó a reclamar este proceso. Manifestaron su desacuerdo con estos procedimientos y trataron de meter algunas otras propuestas. Con estos reclamos también empezaron contrareclamos y todo esto ocupó mucho tiempo, hasta la hora de la comida. Luego del almuerzo, el sup se puso a hablar, criticando también la influencia no representativa del DF y el Estado de México en la reunión, pero tampoco cuestionando la decisión de hacer la marcha. Sin embargo, metió su propia propuesta para la marcha, jugando un papel interesantísimo entre líder autoritario y, para usar un término que nos explicó Rodrigo Ibarra, un “anciano” que busca alternativas incluyentes que faciliten la conciliación de la comunidad. O sea que la propuesta del Delegado Zero nunca cuestionó la marcha, pero al mismo tiempo pidió que los bloques regionales se reunieran para escribir el texto que se iba a leer en el Zócalo al día siguiente, y también que eligieran las personas que lo iban a leer. Desde luego, la figura moral de Marcos consiguió un casi consenso, aunque había borrado varias contrapropuestas que andaban por allí. Y la verdad es que, para mí, las reuniones en bloque fueron la parte más chida, porque facilitó la participación de las personas que aún no habían ofrecido sus comentarios y sus voces dentro del auditorio enorme. Nos pusimos las pilas y empezamos a trabajar, democráticamente y de abajo… pero impulsados por el “líder” (o anciano). Una tensión fascinante.

Y después de todo esto, la marcha estuvo buenísima, muy divertida, llena de movida, y empoderadora. Sin problemas por parte de la policía. Hay algunas fotos aquí, y tal vez vienen más. Y a ver que dice Alejandro...

El Defectuoso

Voy a dividir las entradas sobre el D.F. en varias partes, para no agobiar a nuestros humildes lectores. Aquí va la parte más turística, digamos.

A estas alturas llevamos más o menos una semana y media en el D.F. La ciudad sigue igual, enorme, agobiante, llena de movida, divertidísima. Sin embargo, la entrada a la ciudad no fue tan espectacular como me la imaginaba, como nada más llegamos a Ciudad Satélite, en el Estado de México al norte del propio defectuoso. Lejos de todo. Demasiado lejos. Así que nos mudamos después de varios días más para el centro, en la colonia Roma. A partir de allí, cambiando frecuentemente de casa por factores externos (como por ejemplo el hecho de que venció el alquiler de una amiga en donde nos quedabamos), un desmadre con todas las cosas de la moto...

... y la moto. Ésta es otra historia. Resulta que el ventilador que compramos en Tucson ya hace casi un mes no resolvió el problema. Ahora hasta el motor de ventilador tenemos que cambiarlo. Entregamos la moto al mecánico hace una semana, y por lo visto está lista para recoger hoy.

Hemos conocido a un montón de gente super buena onda, igual que el resto del viaje pero como todo el mundo que habíamos conocido venía para acá de todos modos, es hasta más chido el ambiente ahora. El D.F., sobre todo ahora con la Otra en plena marcha, ha servido como una especie de imán que atrae a toda la gente chida metida en la misma onda. Incluso la gente que conocíamos en el “otro lado” ha venido. Por ejemplo, los últimos días hemos estado quedando en el departamento de un amigo que conocimos en Arizona durante la caminata, buenísima onda.

También, viejos amigos. No toda la banda junaxera pudo venir, pero por lo menos algunas personas: Ion, Moni, Ceci, Vanessa, y yo pudimos vernos y tomar unas chelas. Sin berenjenas, pero ni modo. Y la mamá de Alejandro ha venido a visitar, y para él ha sido muy bueno verla.

Total que el regreso al monstruo ha sido genial.

A estas alturas llevamos más o menos una semana y media en el D.F. La ciudad sigue igual, enorme, agobiante, llena de movida, divertidísima. Sin embargo, la entrada a la ciudad no fue tan espectacular como me la imaginaba, como nada más llegamos a Ciudad Satélite, en el Estado de México al norte del propio defectuoso. Lejos de todo. Demasiado lejos. Así que nos mudamos después de varios días más para el centro, en la colonia Roma. A partir de allí, cambiando frecuentemente de casa por factores externos (como por ejemplo el hecho de que venció el alquiler de una amiga en donde nos quedabamos), un desmadre con todas las cosas de la moto...

... y la moto. Ésta es otra historia. Resulta que el ventilador que compramos en Tucson ya hace casi un mes no resolvió el problema. Ahora hasta el motor de ventilador tenemos que cambiarlo. Entregamos la moto al mecánico hace una semana, y por lo visto está lista para recoger hoy.

Hemos conocido a un montón de gente super buena onda, igual que el resto del viaje pero como todo el mundo que habíamos conocido venía para acá de todos modos, es hasta más chido el ambiente ahora. El D.F., sobre todo ahora con la Otra en plena marcha, ha servido como una especie de imán que atrae a toda la gente chida metida en la misma onda. Incluso la gente que conocíamos en el “otro lado” ha venido. Por ejemplo, los últimos días hemos estado quedando en el departamento de un amigo que conocimos en Arizona durante la caminata, buenísima onda.

También, viejos amigos. No toda la banda junaxera pudo venir, pero por lo menos algunas personas: Ion, Moni, Ceci, Vanessa, y yo pudimos vernos y tomar unas chelas. Sin berenjenas, pero ni modo. Y la mamá de Alejandro ha venido a visitar, y para él ha sido muy bueno verla.

Total que el regreso al monstruo ha sido genial.

South Central Farm Update

At the Asamblea Nacional in Mexico City, I interviewed Debbie X., from L.A., who collaborates with the farm. She passed on some fascinating updates.

We know that the farmers were officially evicted on June 13 by a group of police, private security guards, and bulldozers that arrived at the behest of land speculator Ralph Horowitz, who wants to turn the farm into a warehouse for Wal-Mart. The question we have to ask now is if, and how, the farmers are continuing the struggle.

According to Debbie, they’re not giving up. First, the vigils outside the farm continue. At the plantón, there are perpetually 20-50 people there around the perimeter of the fence, 24 hours a day. The farmers are still holding their Sunday farmers’ market (although noone I talked to seems to know exactly where the produce is coming from). What’s even more interesting is that they’ve begun to cultivate the strip of land just outside the fence, as a way of maintaining the farm and its culture even after being violently ejected from the original space.

This brings me to another issue. On hearing about the bulldozers, I’d imagined that the farm had been completely destroyed. But Debbie says no: “It’s definitely still there.” Parts have been razed, it seems, but other areas remain just as they were before the eviction. The point is that the farm is recoverable, that there hasn’t been permanent damage.

Farmers have also salvaged seeds from their plots. The crops under cultivation, mainly Mesoamerican plants less common in the U.S., represent not only a source of food, income, and culture, but also an ecological heritage and a form of resistance against biotech giants like Monsanto and Novartis. And, to further link the farm with the Other Campaign, seeds have apparently been sent to Atenco for productive safekeeping.

Finally, Debbie highlighted two more strategies of resistance. First, as we’ve already seen, there’s a court date on July 12, when lawyers for the farm will launch a lawsuit against Horowitz charging that the way he acquired the land from the city was illegal. But there’s another strategy, which is an application to have the city officially recognize the farm as a historical monument. Alone, this probably wouldn’t work, and Debbie admitted that the city thinks it’s a “joke.” But the idea is that in combination with these other avenues of resistance, the city may have to back down.

More information from the South Central Farmers here.

We know that the farmers were officially evicted on June 13 by a group of police, private security guards, and bulldozers that arrived at the behest of land speculator Ralph Horowitz, who wants to turn the farm into a warehouse for Wal-Mart. The question we have to ask now is if, and how, the farmers are continuing the struggle.

According to Debbie, they’re not giving up. First, the vigils outside the farm continue. At the plantón, there are perpetually 20-50 people there around the perimeter of the fence, 24 hours a day. The farmers are still holding their Sunday farmers’ market (although noone I talked to seems to know exactly where the produce is coming from). What’s even more interesting is that they’ve begun to cultivate the strip of land just outside the fence, as a way of maintaining the farm and its culture even after being violently ejected from the original space.

This brings me to another issue. On hearing about the bulldozers, I’d imagined that the farm had been completely destroyed. But Debbie says no: “It’s definitely still there.” Parts have been razed, it seems, but other areas remain just as they were before the eviction. The point is that the farm is recoverable, that there hasn’t been permanent damage.

Farmers have also salvaged seeds from their plots. The crops under cultivation, mainly Mesoamerican plants less common in the U.S., represent not only a source of food, income, and culture, but also an ecological heritage and a form of resistance against biotech giants like Monsanto and Novartis. And, to further link the farm with the Other Campaign, seeds have apparently been sent to Atenco for productive safekeeping.

Finally, Debbie highlighted two more strategies of resistance. First, as we’ve already seen, there’s a court date on July 12, when lawyers for the farm will launch a lawsuit against Horowitz charging that the way he acquired the land from the city was illegal. But there’s another strategy, which is an application to have the city officially recognize the farm as a historical monument. Alone, this probably wouldn’t work, and Debbie admitted that the city thinks it’s a “joke.” But the idea is that in combination with these other avenues of resistance, the city may have to back down.

More information from the South Central Farmers here.

Tuesday, June 27, 2006

Queretaro

[We're a little behind schedule with the blog. Even though we're in D.F., I wanted to catch us up a little on the places we'd hit earlier.]

The “desayuno” wasn’t exactly a breakfast as I understood the word’s direct translation. Brunch, I suppose, would be a little bit closer. Still, it can’t be a brunch, for starters, if it begins at 9 am.

The map, I think, will go down in history as perhaps the worst map ever drawn.* Here’s a picture of it:

It’s supposed to represent how to get from Alejandro’s cousin’s house, on the west side of Querétaro, to Juan Pablo’s house on the east side. Somehow, mysteriously, we made it there without too many problems. Juan Pablo, Abelardo, and Mirta were there, just beginning to prepare the food. Mirta was chopping tomatoes, onions, and jalapeño chiles for pico de gallo. They immediately served us a dark, rich espresso from a percolator and told us the plan: gorditas.

It’s supposed to represent how to get from Alejandro’s cousin’s house, on the west side of Querétaro, to Juan Pablo’s house on the east side. Somehow, mysteriously, we made it there without too many problems. Juan Pablo, Abelardo, and Mirta were there, just beginning to prepare the food. Mirta was chopping tomatoes, onions, and jalapeño chiles for pico de gallo. They immediately served us a dark, rich espresso from a percolator and told us the plan: gorditas.

Masa was bought—a multicolored masa, seemingly made with many varieties of corn, reds, blues, greens, in addition to the standard yellow. (Perhaps some lard as well, though I followed my usual “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.) The gordita-making process looks relatively easy, and I was surprised at how pupusa-like these little corn dumplings are.

We also interviewed Alexis Benhumea’s uncle, Oscar. Alexis was a economics student, adherent to the Other Campaign, who was shot in the head with a teargas canister during the police invasion of Atenco on May 4. He fell into a coma and his father called an ambulance, but the police wouldn’t let it into the city. Alexis laid, slowly dying, there for about 11 hours before finally an American journalist named John Gibler (and others) rented a van to take him to the hospital. He survived there for about a month, but died on June 7. This interview appears in a radio segment that aired yesterday on Flashpoints.

* Followed more or less closely by pencil shavings in a bag.

The “desayuno” wasn’t exactly a breakfast as I understood the word’s direct translation. Brunch, I suppose, would be a little bit closer. Still, it can’t be a brunch, for starters, if it begins at 9 am.

The map, I think, will go down in history as perhaps the worst map ever drawn.* Here’s a picture of it:

It’s supposed to represent how to get from Alejandro’s cousin’s house, on the west side of Querétaro, to Juan Pablo’s house on the east side. Somehow, mysteriously, we made it there without too many problems. Juan Pablo, Abelardo, and Mirta were there, just beginning to prepare the food. Mirta was chopping tomatoes, onions, and jalapeño chiles for pico de gallo. They immediately served us a dark, rich espresso from a percolator and told us the plan: gorditas.

It’s supposed to represent how to get from Alejandro’s cousin’s house, on the west side of Querétaro, to Juan Pablo’s house on the east side. Somehow, mysteriously, we made it there without too many problems. Juan Pablo, Abelardo, and Mirta were there, just beginning to prepare the food. Mirta was chopping tomatoes, onions, and jalapeño chiles for pico de gallo. They immediately served us a dark, rich espresso from a percolator and told us the plan: gorditas.Masa was bought—a multicolored masa, seemingly made with many varieties of corn, reds, blues, greens, in addition to the standard yellow. (Perhaps some lard as well, though I followed my usual “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.) The gordita-making process looks relatively easy, and I was surprised at how pupusa-like these little corn dumplings are.

We also interviewed Alexis Benhumea’s uncle, Oscar. Alexis was a economics student, adherent to the Other Campaign, who was shot in the head with a teargas canister during the police invasion of Atenco on May 4. He fell into a coma and his father called an ambulance, but the police wouldn’t let it into the city. Alexis laid, slowly dying, there for about 11 hours before finally an American journalist named John Gibler (and others) rented a van to take him to the hospital. He survived there for about a month, but died on June 7. This interview appears in a radio segment that aired yesterday on Flashpoints.

* Followed more or less closely by pencil shavings in a bag.

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Guanajuato

Compas, disculpen el inglish, pero para dar continuidad a los escritos de Daniel, esta va en la lengua del tío sam (o bien de shakespeare, si prefieren), y en breve me redimiré de la displiscencia escribiendo una larga crónica en español.

Guanajuato, colonial gem in the Bajío, with its narrow alleys and its network of underground streets, is a splendid city that proved to be a laberynthine nightmare with an overheating motorcycle, that somehow, miraculosuly, made it to the hostel where we finally let it rest, tied to the bars of a colonial window.

We got here after heartfelt despedidas from the compañeros in Zacatecas, with whom in two days we managed to build friendships that were hard to part from. Our last night there we had a long conversation with them and with teachers who were doing a several day sit-in in front of the city hall, in protest against educational reforms that threaten to reduce an already deficient curriculum in history and for higher wages. It was a fascinating point of contact between La Otra in Mexico and La Otra on the other side of the border, and in the interchange we all learned from different perspectives and the challenges of thinking trasnationally. Their questions about identity reminded me of a commentary by José Rabasa about zapatismo and its redefinition of the concept of nation: where does the "Mexican" nation start and end. And it is curious to think that, while the realities of immigration and "globalization" are imploding the notions of nationhood, physical walls are constructed in a sort of desperate attempt to elude the realities of our times.

Today we went to see two compañeras from Irapuato, who gave us a rather different perspective of the Other Campaign. This is one of the states that the zapatista caravan did visit, the first one in our trip. The story of conflicts between the various organizers told by the compañeras speaks of a number of challenges faced by such an ambitious and innovative movement. On one hand, the Other Campaign is in principle inclusive, and its novelty resides precisely in that it does not guided by a single ideology, a single principle, a single vanguard. As such, political activists from many different affiliations and ideologies participate, which has led long-time zapatista supporters like John Ross to turn his back on the movement at the (admittedly unsightly) sight of stalinist posters held up by members of the communist party. On the other hand, as we discussed with John Sullivan in Zacatecas, social movements in Mexico have been traditionally coopted or infiltrated by political parties, which bring to them their own agendas and their own interests, and because of that the Other Campaign has been adamant in its refusal to admit activists from the PRD, who have repeatedly tried to have an influence in it. These two principles (inclusiveness and rejection of political parties) are rather difficult to conciliate, and often lead to conflicts such as those apparently experienced in Irapuato.

And yet we also heard stories that are representative of zapatismo's ability to serve as a point of contact for people and social segments that would otherwise not find a way to interact. Every Saturday, the colectivo sets up banners and gives out information in the kiosk of the main square, and have long talks with people of every sort, supporters and opposers. They spoke of two women who had a long, heated discussion: a pregnant prostitute and an religious, middle class woman. In a society where religious intolerance and social prejudice are so ingrained, this sort of communication is almost unheard of. That such a conversation might take place and actually lead to some kind of understanding, is more than merely a quaint anecdote. The physical and psychological walls that increasingly separate social classes are one of the most unfortunate tendencies in contemporary Latin American societies, and are at the root of much of the social violence increasingly experienced in the cities.

Guanajuato, colonial gem in the Bajío, with its narrow alleys and its network of underground streets, is a splendid city that proved to be a laberynthine nightmare with an overheating motorcycle, that somehow, miraculosuly, made it to the hostel where we finally let it rest, tied to the bars of a colonial window.

We got here after heartfelt despedidas from the compañeros in Zacatecas, with whom in two days we managed to build friendships that were hard to part from. Our last night there we had a long conversation with them and with teachers who were doing a several day sit-in in front of the city hall, in protest against educational reforms that threaten to reduce an already deficient curriculum in history and for higher wages. It was a fascinating point of contact between La Otra in Mexico and La Otra on the other side of the border, and in the interchange we all learned from different perspectives and the challenges of thinking trasnationally. Their questions about identity reminded me of a commentary by José Rabasa about zapatismo and its redefinition of the concept of nation: where does the "Mexican" nation start and end. And it is curious to think that, while the realities of immigration and "globalization" are imploding the notions of nationhood, physical walls are constructed in a sort of desperate attempt to elude the realities of our times.